John Montgomery—Local aviation pioneer that history nearly forgot (part 1)

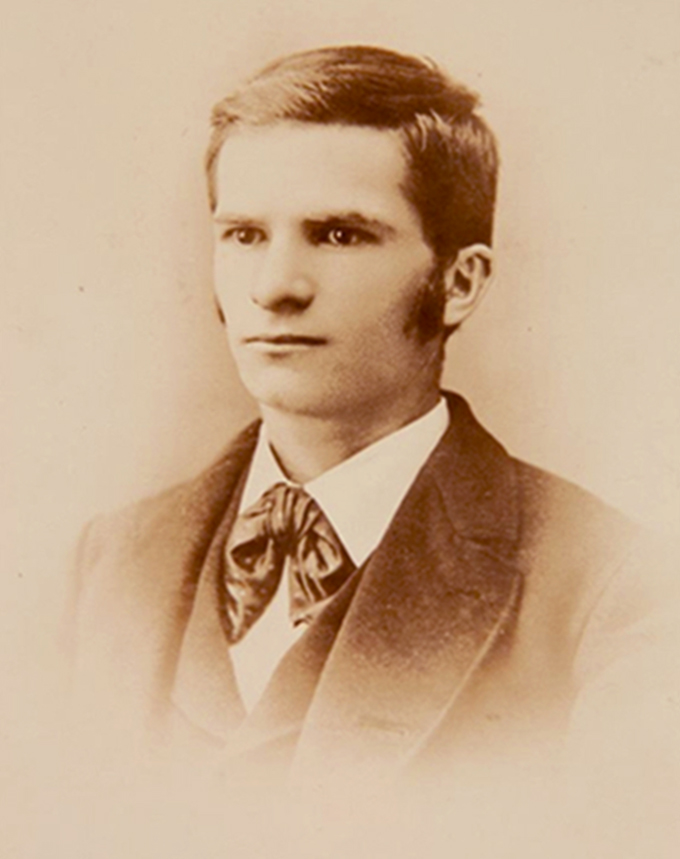

The second oldest village in The Villages bears the name of a local aviation pioneer who was cut short in his rise to international fame by a tragic test flight accident that claimed his life. John Joseph Montgomery (1858-1911) was an inventor, physicist, engineer and professor at Santa Clara University, best known for his aerodynamic research on controlled, heavier-than-air flying machines. Many of the tests of his gliders (which he referred to as “aeroplanes”) took place within a couple miles of The Villages on Montgomery Hill, now adjacent to the Evergreen Valley College.

In words on a historic marker in Aptos, California, Montgomery’s history is summed up in one concluding sentence: “Called the ‘Father of Basic Flying,’ his successes and contributions to the development of flight were heralded by the world’s press at the time, but are now largely forgotten.”

Montgomery, a native Californian, began testing glider designs as a kid based on his observation of birds’ wings. As his interests became goals, his early field tests took place near his family farm on Otay Mesa south of San Diego in the 1880s.

Montgomery had a brilliant scientific mind that he directed toward the development of heavier-than-air gliders that could be controlled by a pilot aboard the craft. His studies were influenced by earlier European aviation pioneers. These early pioneers were the subjects of an inspirational lecture he attended at the International Conference on Aerial Navigation in Chicago in 1893.

Montgomery’s early flying models employed control devices that are now common components of modern airplanes, such as moveable elevators, pilot-operated trailing edge flaps on wings, aft tail sections, cable-controlled ailerons, and cambered wings for enhanced lift—similar to the concave shape of birds’ wings based on his studies of large soaring birds.

From 1884 to 1886, Montgomery tested experimental gliders launched from the edge of Otay Mesa where he tried to gain control over the variables for sustained flight. As a result of these tests, he developed an inclined launch ramp system with wooden rails to direct the gliders into the air. This launch system was later employed on Montgomery Hill in Evergreen. He made many test flights, some of them reaching distances of 600 feet. These early flight tests provided marginal results in balance and equilibrium, so in search of perfection he returned to controlled trials in the laboratory—designing a proto-wind tunnel, using smoke to show the flow of air around his experimental wings compared to various bird wings. Montgomery was a tenacious, natural-born scientist.

In 1893, Montgomery attended the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago intending to hear a lecture on electricity by Nikola Tesla, but encountered the chairs of the International Conference on Aerial Navigation who invited him to give two lectures about his studies of flight, which eventually became an article that was published in the July 1894 edition of Aeronautics.

Returning to his wind test chamber, Montgomery conducted further experiments into the physics of air flow over wings to maximize lift. From these results he developed a theory of lift based on vorticity—what modern aerodynamicists refer to as “circulation theory.”

Montgomery supplemented his aeronautical research with work in other branches of science, including electricity, communication, astronomy and mining. He received four patents (among his many others) for improvements in the efficiency of petroleum burning furnaces. Looking over his many accomplishments, it is obvious that Montgomery had incredible energy, curiosity and an intense drive to pursue his many interests.

In 1897 Montgomery took a teaching position at Santa Clara College (now Santa Clara University) and began to study wireless telegraphy and make improvements on a reproduction of a Marconi Wireless radio built by Father Richard Bell. They were first to successfully transmit messages from Santa Clara College to San Francisco. Montgomery also patented two gold concentrator devices to assist miners in extracting gold from beach sand. It seemed Montgomery could do almost anything he set his mind to.

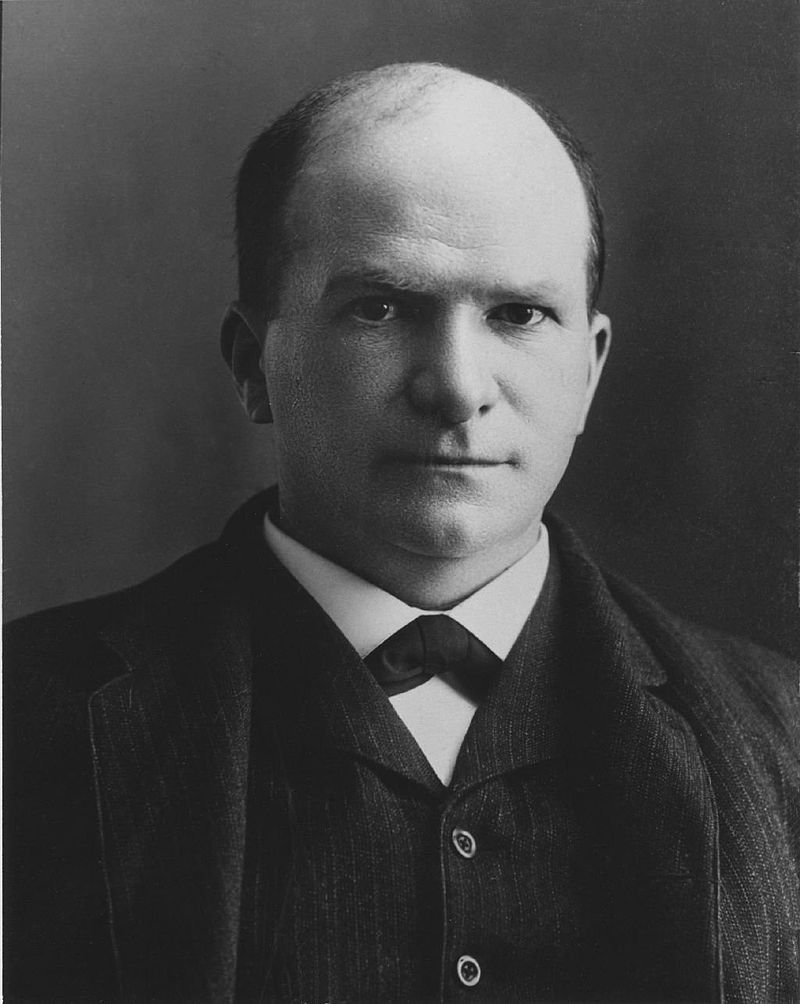

In 1903 Montgomery began collaborating with balloonist Thomas Scott Baldwin who was working on improving the design of dirigible propellers.

1903 was also the year that the Wright Brothers achieved the milestone of their first successful powered flight. By that time, Montgomery’s gliders were nimbly performing figure eights while the Wright Flyer could only make marginal maneuvers. And Montgomery’s gliders were able to make sustained flights. Another significant difference between the two design teams was the Wright Brothers’ flat wings versus Montgomery’s cambered wings.

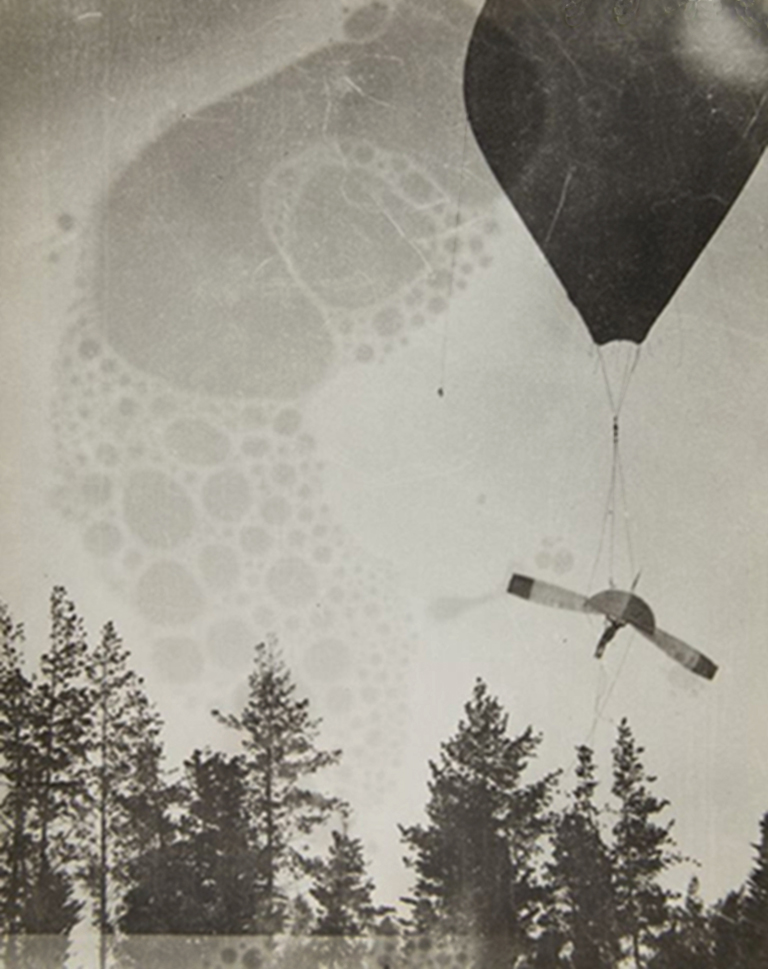

In 1904, Montgomery and Baldwin entered into a business arrangement to hold public exhibitions with manned Montgomery gliders launched at high altitudes from unmanned Baldwin balloons (bordering on showmanship). Baldwin broke their agreement by using the improved propellers on his motorized balloons, and personally entered and won first place in an aeronautics competition at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair. This betrayal caused years of bad blood between the two.

In 1904 and 1905 Montgomery conducted tests of a tandem-wing glider, the Montgomery Aeroplane in Aptos, California—using the precursor to the word “airplane.” By then Montgomery’s experiments attained worldwide acclaim and after one of the test flights he held a press conference and announced a patent application for his aeroplane and methods of wing warping. Montgomery’s fame was expanding as he worked toward his dream of controlled, powered flight.

Montgomery and his colleagues provided a public demonstration of the Montgomery Aeroplane, rechristened as The Santa Clara in honor of Santa Clara College where the spectacle took place high above the campus in full view of a crowd of spectators and members of the press. Montgomery’s colleague, Daniel J. Maloney, piloted the craft, which was released from a balloon about 4,000 feet aloft. Maloney performed a series of pre-determined maneuvers and ended the spectacle with a soft landing nearby. The flight received world-wide accolades and became a milestone event in the annals of aeronautics.

In July of 1905, Maloney was killed when a rope from the balloon damaged the glider as it was released causing the craft to plummet to earth. Despite the dangerous nature of the balloon experiments, Montgomery continued them with other pilots.

Regardless of the hazards of experimental flight, it was the 1906 San Francisco Earthquake that became the biggest setback for Montgomery’s research, stalling his glider trials until 1911.

Montgomery renewed his experimentation with a revamped control system on his glider to remedy the problematic pitch and roll issues by adding wing warping and a fixed tail assembly resembling that of modern airplanes. Montgomery’s goal with this new design was to eventually add a motor and apply for a patent. This glider, The Evergreen, the namesake of our oak-scattered hills, was flown in more than 50 trials by Montgomery and another pilot.

Seated in the pilot’s seat on October 31, 1911, Montgomery launched the craft and attempted to land the Evergreen at low speed but stalled because of air turbulence. The craft slid sideways crashed hard and Montgomery died at the scene from a head injury caused by a protruding bolt on the glider frame. His life and legacy ended on the hillside that bears his name, almost a stone’s throw from The Villages.

John J. Montgomery is buried at the Holy Cross Cemetery in Colma, California on the San Francisco Peninsula.

His absence in the field of aeronautics probably contributed to the Wright Brothers’ rise in fame years after their successful Kitty Hawk, North Carolina motorized flight.

Had John Montgomery been able to continue with his research, perhaps his rising star would have matched or even eclipsed the fame of the Wright Brothers.

—Series compiled and written by S.R. Hinrichs

The Roots of Evergreen series will be published the third week of each month and posted in the Online Villager. The next article will feature John Montgomery’s legacy.