William Wehner laid out $20,000 for the construction of his handsome new Evergreen home and named it Lomas Azules (Blue Hills). It was a grand, three-story wooden house on a stone foundation, a unique example of a late Queen Anne architectural style. Completed in 1891, the Wehner’s mansion was set on a knoll overlooking the picturesque Evergreen Valley stretching out below. There were eight fireplaces and indoor bathrooms—early design innovations by the prestigious Burnham and Root architectural firm of Chicago. The repeated round arches on the exterior of the mansion’s enclosed sun porch mirror similar arches on Burnham and Root skyscrapers in cities across the nation. Directly behind the house was a “summer kitchen” separate from the house, which still stands. Wehner’s ranch, named Highland Vineyards, was mentioned in the San Jose Daily Mercury in 1901 as “…the finest and most beautiful vineyard in California.” In Wehner’s original layout, a road snaked up to the house through a stone entry gate that still stands in the middle of the golf course by the ninth tee. A few of the old trees that were next to the road are still present.

The mansion was designated as an Historic Landmark Building by the city of San Jose on October 17 of 1989.

A rare residential design by the Chicago School titans

With his business success mostly achieved in Chicago, William Wehner associated with many businessmen who later became well known in the 20th century. He hired two architectural titans, Daniel Hudson Burnham and John Wellborn Root, partners in the architectural firm of Burnham and Root, to design his California home. At that time, the firm was also commissioned to design the Chronicle Building and the Mills Building in San Francisco.

The Burnham and Root firm was one of Chicago’s most influential innovators during that city’s massive 19th century building boom. Later referred to as the Chicago School, the city’s architects were experiencing a golden age of urban design as the Chicago skyline stretched toward the sky. And Burnham and Root had major roles in revolutionizing Chicago architecture, pioneering tall buildings with innovative foundations and structural systems.

Burnham continued on with the firm, known as D.H. Burnham and Company, after Root’s untimely death, at age 41, in 1891—the year the Wehner Mansion was completed.

The Wehner Mansion was an anomaly because the firm had moved away from residential structures, preferring to concentrate on the design of commercial buildings and skyscrapers and innovative urban plans. The Wehner home is the only known example of a residential design by the firm in all of California. Most likely Wehner and the architects had professional and personal interactions during their time in Chicago. It was also speculated that William Wehner and Willis Polk, the famous and prolific West Coast architect, also from Chicago, may have had earlier associations. Polk came to California about the same time as Wehner and became the head of the San Francisco office of Burnham and Root. Polk is well known in the Bay Area and California for his numerous monumental buildings.

While Burnham and Root’s early home designs were primarily for wealthy clients, the firm was better known for its tall buildings. Burnham and Root had a significant influence on the skylines of every modern city on earth because of their innovations in steel-framed, high-rise structures that allowed modern building frames to bear the weight of extremely tall structures. It also pioneered the development of early glass curtain sheathing on large buildings, which vastly reduced the weight of building coverings, further facilitating the development of ultra high-rise structures. The firm also explored innovative “floating” raft foundations to compensate for Chicago’s poor soil conditions and developed complex hybrid structural systems—their buildings pushed the limits of materials and technology available in the late 19th century. At the time of Burnham’s death in 1912, his firm had become the largest in the country with more than 200 employees.

Anyone who has taken a modern architecture class in college has surely heard the names of Burnham and Root because of their milestone skyscraper designs. Some of these groundbreaking designs include:

• The 10-story Montauk Building, Chicago, 1882.

• The Rookery, 1886, one of the oldest high-rise buildings in Chicago.

• The Reliance Building, Chicago, 1891, an early precursor to modern glass-sheathed skyscrapers.

• The Monadnock Building, 1889-1891, which rose up 16 stories—the last of Chicago’s great masonry skyscrapers, considered the tallest load-bearing masonry structure ever constructed.

• The Rand McNally Building, Chicago, 1889, at 16 stories it was the world’s first all-steel framed skyscraper.

• The Masonic Temple, 1892, Chicago’s first 20-story building—the tallest in Chicago from 1892 into the 1920s.

The firm also designed buildings in cities across the nation, including:

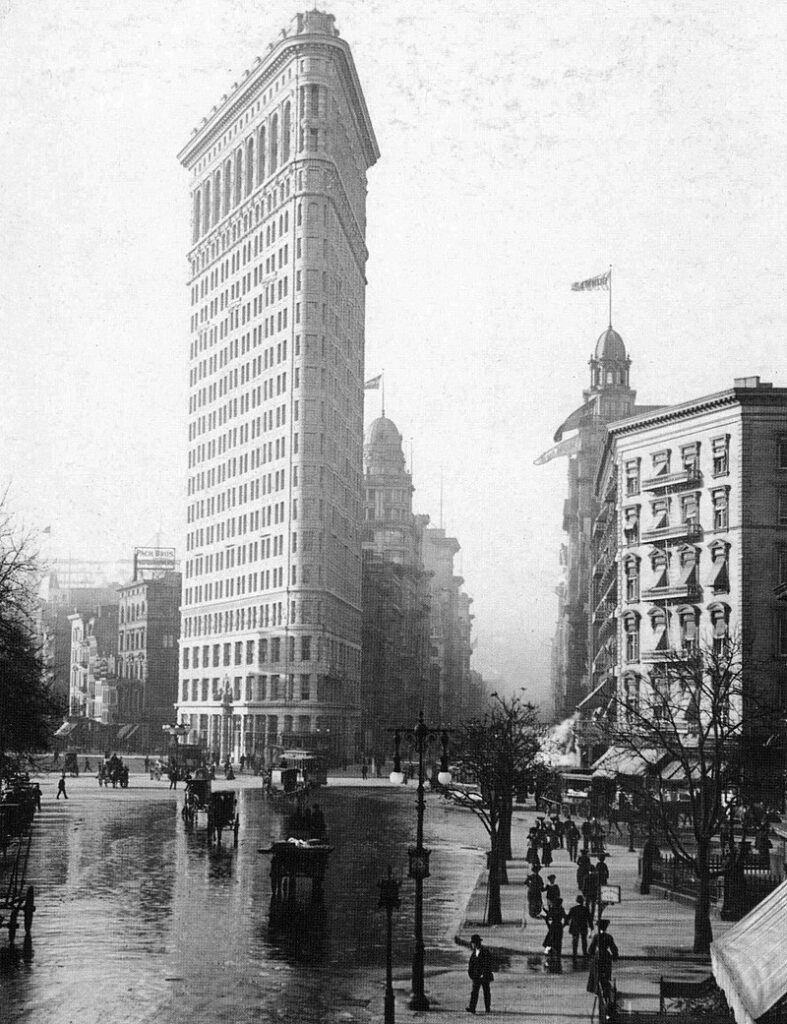

• The iconic 22-story Flatiron Building, New York City, 1922, called in its early days, “Burnham’s Folly.”

• Union Station in Washington D.C.

• The Romanesque Revival styled Mills Building and Tower, in San Francisco’s financial district.

• Montezuma Castle hotel, Las Vegas, New Mexico, a unique, ornate Queen Anne style.

The firm also designed the plans for the World’s Columbina Exposition, Chicago, 1893

The Chicago 1893 World’s Fair “White City” complex, with the Palace of Fine Arts as centerpiece—now the Griffin Museum of Science and Industry, the only surviving building from the fair.

The firm also designed numerous urban plans for cities across the nation.

—Series compiled and written by S.R. Hinrichs

The Roots of Evergreen series will be published the third week of each month and posted in the Online Villager. The next article will feature the beginning of the Evergreen community.